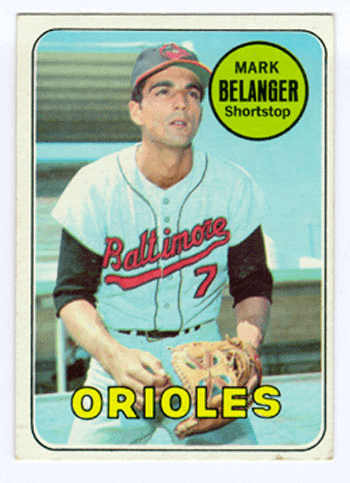

Over six feet tall and a trim 170 pounds, Mark Belanger had the fearless, Mediterranean good looks of a matador and played shortstop for a baseball dynasty of yore known as Earl Weaver’s Baltimore Orioles.

With a .977 fielding average and eight gold gloves over 18 seasons – all but one of them for the black and orange on the Patapsco – virtually nothing got by Mark Henry Belanger.

To play day-in-and-day-out in the big leagues for that long with a lifetime batting average of .228 (select are those who saw a Belanger hit a home run, it only happened 20 times) you had to be flawless in the field.

“Smooth as silk,” said Charlie Stein, 58, a die-hard Orioles’ fan from Catonsville who grew up close enough to Memorial Stadium to hear the cheers from the stands.

“Belanger made it all look easy,” said Stein. “He played the game right, without being showy. When he stretched out deep in the hole you knew he’d snag the ball and make the throw. His range made the whole infield better.”

That infield included immortal Hall of Famer Brooks Robinson – widely regarded as the best third baseman in the history of the game; and future Orioles manager Davey Johnson at second base.

Rounding out the infield on those glory teams (three consecutive trips to the World Series between 1969 and 1971 and all the marbles in 1970) was first baseman “Barbecue Boog” Powell.

At 7 p.m., on Saturday, March 28 – with Opening Day 2015 just a week away – the family of Mark Belanger will gather at an East Baltimore hot dog joint for a Catholic school fund-raiser in the shortstop’s name.

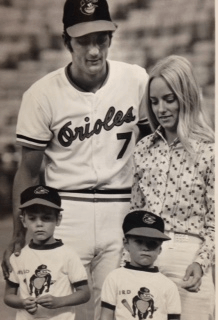

Dee Belanger, Belanger’s high school sweetheart in his native Pittsfield, Massachusetts and his widow after his death from cancer at age 54 in 1998, will attend with sons Rob and Rich.

Back in 1969, when Weaver’s Dreadnought Birds were torpedoed in the World Series by Gil Hodges’ Miracle Mets, son Rob was just three weeks old and wrapped in a blanket at Shea Stadium on Dee’s lap. Rich was a little more than a year old.

On the field, watched by his French-Canadian father Edward and Italian-American mother Maria along with Dee’s parents, Belanger batted .200 with one RBI and typically made no errors. The heavily-favored Orioles lost the series four games to one.

“Nobody could believe they lost to the Mets,” said Dee. “But it was meant to be.”

The “Mark Belanger Festival” at G&A Coney Island Hot Dogs in the heart of Highlandtown will benefit Mother Seton Academy, a tuition-free middle school for co-eds from Baltimore’s less fortunate neighborhoods.

Students from the school will be on hand to sing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” and the National Anthem will be sung by Baltimore School for the Arts opera major Dije Coxson.

Belanger t-shirts will be on sale for $22, hot dogs with “the woiks” will go for a buck or two and there will be readings of baseball stories and National Pastime poetry by Jen Michalski, Sarah Jane Miller and former Baltimore Sun rewrite man David Michael Ettlin.

Of special note will be a performance of “Thank God I’m A Country Boy” by Rich Belanger.

The top of the charts John Denver hit from 1975 – played during the 7th inning stretch at Orioles’ home games for the past 40 years – came about because of Dee Belanger, a big fan of the singer.

Given a pass to meet Denver backstage after a concert, Dee was introduced to John Martin Sommers, who wrote the song. The first thing Sommers said to Dee was the same thing she’s been hearing since the Blade broke into the Major Leagues with the Orioles in 1965: “Are you related to Mark Belanger the baseball player?”

“I usually say, ‘Was he a golfer?’” laughed Dee, whose name for her husband if they were in public was “George” to deflect unwanted attention.

But to Sommers she told the truth and they became friends. About this time, the Orioles were trying to lure more fans to their old home field, Memorial Stadium.

The team fell short in 1974, attracting a mere 962,572 fans. The next season, said Shaver, the team tried attract younger fans by changing the music played over the loudspeakers and drew 1,002,157. The trend was away from traditional ballpark organ music and toward the pop charts.

Dee suggested “Thank God I’m a Country Boy,” it was played during the 7th inning stretch and remains there today, an enduring, unlikely hillbilly anthem in the midst of the majority African-American city of Crabtown.

During the 1983 World Series

Denver died in 1997 after crashing his experimental plane into Monterey Bay, a year before Belanger died at the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

-o-

Mark Belanger wore No. 7 for the Baltimore Orioles for parts of three decades.

The first modern-era Oriole to wear the number was first baseman Frank Kellert [1924-to-1976] in the team’s 1954 return to the major leagues. Though the number has not been retired by the team, no one has worn it since the death of former manager Cal Ripken, Sr. in 1999.

In his time as “the most electrifying defensive shortstop of his generation” (according to baseball writer Frank Vaccaro), Mark Belanger had three vanity plates on his automobiles: Birds -7, Glove-7, and Blade-7.

“Belanger was proof that excellence in one specific thing – fielding – would be valued more than mere competence in many things,” said Leo Ryan, Jr., 56, a District Court of Maryland judge who grew up rooting for the Orioles at Memorial Stadium with his father, Leo, Sr., a Teamster.

“The Blade was quiet, he was tough and he did his job with consistent excellence,” said Ryan. “He embodied what Baltimore knew about itself.

This brought back so many memories. Good writing. Glad Belanger is not forgotten. I particularly like the beginning, describing Mark as having the looks of a matador. That he did. Yes indeed, from deep in the hole on the outfield grass…no need to worry. He always got the job done.